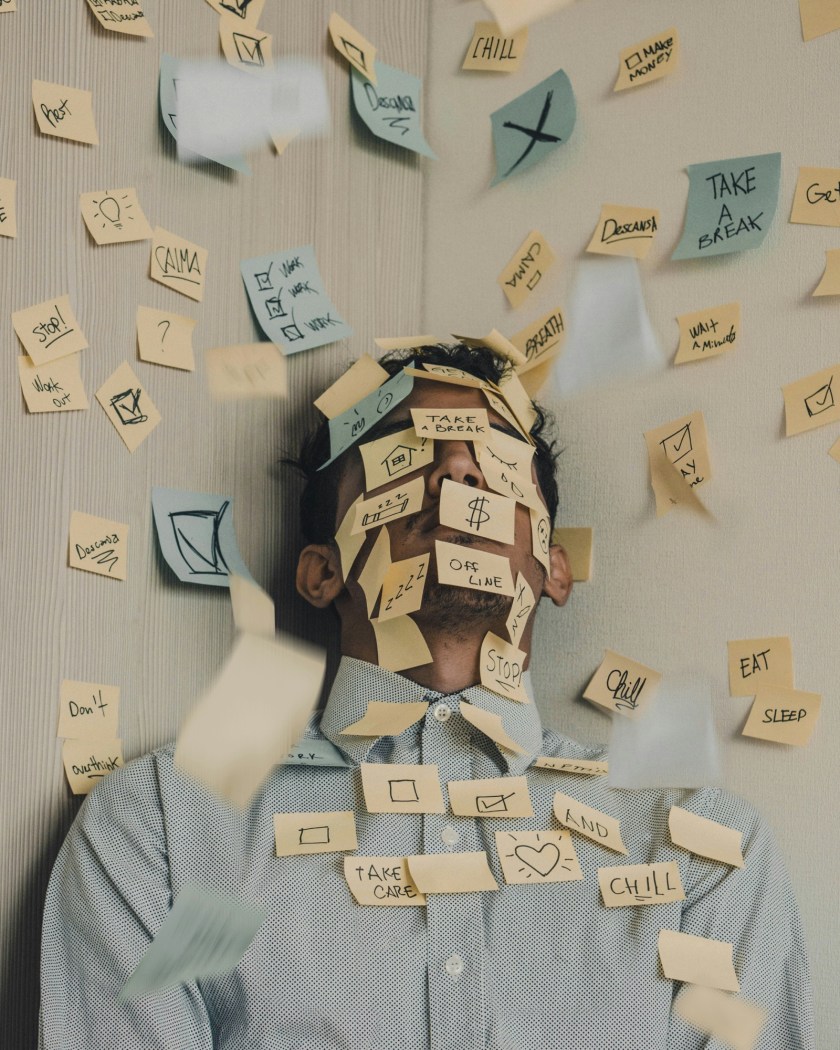

Another view of inclusion or lack thereof.

Much like early years personal experiences sit at the foundation of who I am today, for good or for bad, early professional ones have shaped me into the professional that I am. For good or for bad.

My very first job, at 15, was that of a sales person. In the fresh out of communism Romania, one neighbor had decided to start a small business, opening a small shop close to the neighborhood. So I had my very first summer job selling sweets, cigarettes and other such wonderful products not yet deemed harmful. It was the first job that taught me about a working routine, accountability and dealing with customers. It was the first time I realized what a tragedy it was that I never understood math in school.

As a scholarship student in the US, at 17, I had no source of additional income but babysitting and cleaning homes. I remember looking forward so much more to the paycheck than playing with the kids I was babysitting and home owners standing next to me as I scrubbed their toilets to make sure I did it correctly. The discomfort I felt in these jobs pushed me to want to use my privilege and get as much education as I could so that I could be in a position of choosing my job and not in one where my job would choose me. Knowing what you don’t want to do is sometimes even more valuable than knowing what you do want. It was while cleaning many homes that I gained respect for my colleagues who are custodians and cleaners and when it became impossible for me not to see them in the schools and businesses I have worked in so far. They are silent forces that shape the experiences we have in our workplace more than we care to admit. And so many times taken for granted.

I spent years teaching English to Romanians and Romanian to foreigners who had landed in Bucharest for one reason or another. The daughter of a passionate and very capable English teacher, I presumed it was “a quick way to make a buck.” My mom made it look fun and effortless, after all. Aside from discovering yet another thing I did not want to do, I understood that teaching is a vocation before it is a job, that it requires all of your focus while rewards are seldom guaranteed, that sometimes it equals being asked to move mountains with your mind and potentially the books you have to share. Working in schools all my life, I truly look at my colleagues who are teachers as people with superpowers. And as a parent to a student, I am deeply grateful for people who share of themselves in classroom to mold young minds. We don’t often look this truth in the eye but this world is shaped by teachers so much more every day than they are shaped by millionaires or politicians: by the presence or absence of good and dedicated teachers.

My first job in the realm of international schools was that of high school secretary. 23 years down the line it continues to be the job that has taught me the most and that has helped me be a better manager more than any training or book ever has. I learned to look at events from different angles and consider details, be present in meetings where I had to hear but never share, synthesize what I heard in minutes that made sense months later, it opened my eyes to the amount of work that “just a secretary” is being tasked with every minute of every day and to the importance of this seemingly second hand position. There is a Romanian saying, a bit pejorative to the part of the orthodox wedding ritual, which says that the man is the head of the woman but the woman is his neck, turns the head wherever it needs or wants to make it look. Give me any good school Director and I will show you the amazing support they receive from their secretary. And vice versa.

If there is one thing that has continually saddened me in the international schools that I have either worked in or worked with, is the way “support staff” is perceived, included and valued. Yes, teachers are our superstars, their knowledge, their care and craft are the “product” schools are all about. My hat off to amazing teachers. Try however to do that mighty job without students (who would be brought in potentially by admissions and marketing and helped in by the secretary), try working in a dirty school with leaking faucets and doors and windows that don’t close, work without a computer, a printer, a projector, a scanner, forget security and just let anyone in while you are teaching, let the phones ring and have no secretary available to pick up pieces and bridge gaps, issue invoices every now and then and pay your suppliers when you remember. I promise you that any craft, dedication and love for the profession crumbles under such pressure.

I dream of a place where we look at each other so much more as partners rather than us and them and where we take the time to understand each other and the part we play in designing the experiences that shape the kids we love.